History consultant Kwaku posits that the lack of an acknowledgement of the death of the educationalist, anti-racist and community activist Dame Jocelyn Barrow within any mainstream media over one week after her death, goes to show we’re a long way from African British lives and history being considered British enough.

Written by Kwaku

Photo: © BTWSC, Qubtic Church

Video: © Kwaku

“I also believe that it’s part of our own responsibility as communities, as parents, as elders in our communities to ensure we learn our own history.”

Dame Jocelyn Barrow (15 April 1929 – 9 April 2020), educationalist, racial equality, human rights and community activist.

It was a privilege not only knowing Dame Jocelyn Barrow, but also getting her to contribute to some the community history programmes I worked on for BTWSC, a small London-based voluntary organisation. I will refer to her as Dame, as that is how I addressed her.

One such programme was the ‘Look How Far We’ve Come: Commentaries On British Society And Racism?’ DVD. She and the other contributors, including the likes of equality activists Paul Stephenson and Lord Herman Ouseley; politicians such as Diane Abbott MP, Dawn Butler MP, David Lammy MP, Keith Vaz MP, and Ken Livingston; academics such as Professors Paul Gilroy and Harry Goulbourne; and community activists such as Eric and Jessica Huntley, Lee Jasper, Marc Wadsworth, Toyin Agbetu, Brother Omowale, and Zita Holbourne, spoke about how far Britain had come in dealing with racial issues.

It’s taken Dame’s death for me to think that we certainly have a very long way to go!

Why? This is because it’s just over one week since her death was announced on the Twittersphere, and there’s yet to be a single mention or obituary in any of the British mainstream media. At least two European British public figures who died around the same period have had their deaths highlighted across the mainstream press and broadcast media. It makes one wonder how far African British people must rise within British society, for their passing to be worthy of a mention in the mainstream media.

Thus far, the only places you can find out about Dame’s passing are social media – all-round activist Patrick Vernon and Huffington Post UK reporter Nadine White announced Dame’s death in their April 9 posts; Patrick wrote a Voice online obituary and has also been highlighting his 2018 BHM365 Windush interview with Dame; there’s a notice on the website of the Black Cultural Archives – she served as the organisation’s first patron; plus there’s been some coverage on two BBC local radio African specialist programmes – one news bulletin in Karen Gabay’s two hour The People show on Radio Manchester, and a more leisured interview with Patrick on Dotun Adebayo’s Radio London programme.

Curiously, one of the tweets posted days after the initial announcement was to BBC news reader Naga Munchetty. It read: “I’m bringing to light that @BBCNews @BBCBreakfast is yet to pay any tribute to the iconic Dame Jocelyn Barrow – first black female governor of BBC. Not good!”

As I write, the nation’s broadcaster has not mentioned her passing in the main broadcasts. Interestingly, Dame served as a BBC governor from 1981-88, and was a founding member of the Broadcasting Standards Council from 1989-95.

If the collective memories of today’s broadcasters do not stretch back to the pioneering work Dame did in fighting for racial diversity and equality within the broadcasting industry a quarter of a century ago, at least BBC director-general Tony Hall contributed to a tribute published by The Voice.

A statement from the D-G to the newspaper read: “As the first black woman to become a governor of the BBC, Dame Jocelyn Barrow changed the face of leadership within broadcasting and helped to pave the way for all those that have come after her. Her tireless work to progress race relations in the UK and the profound impact she had on the industry is still felt today.”

A few days ago I got an email from a researcher considering highlighting reggae singer Delroy Washington in a proposed BBC news item on Covid19 deaths. I did point out to him that the BBC was yet to cover Dame’s death. So who knows, something might yet pop up on the main Beeb channels.

Of course, some may argue that we should not even bother with whether or not the mainstream media covers the death of a leader within the African community. I’ll suggest that we don’t lose sleep because it doesn’t happen. However, unlike the supposedly more friendly, leftish press like The Guardian, or the independent and commercial media, the BBC is a national broadcaster which owes its existence to our TV licence fees. One would therefore expect the BBC to devote some of its airtime to touch on items that speak to African British lives and history.

That’s the only barometer by which we can judge whether or not progress has been made towards a more equitable society. An equitable society would not only be aware of, but would also highlight, the various components that make up a multi-racial, multi-cultural Britain. Overwhelmingly focusing on the lives of the proverbial “old, white men” needs to be called out, if we genuinely aim for multi-racial, multi-cultural Britain.

I’ll now come off my soap box, and reflect on Dame. I’ll avoid retreading her vast history, some of which can be found on the internet, from 100GreatBlackBritons to Wikipedia. I’ll focus instead on my engagement with Dame and snippets of less well known information.

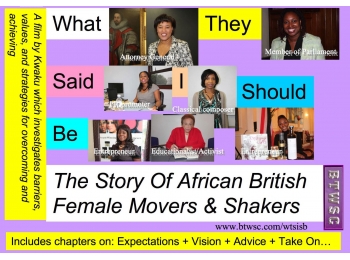

I became aware of Dame in the early 2000s, although at that time she was a distant figure I saw once a year when she was feted as the patron at the AGM of an organisation where my wife worked. Then in 2009, as a counter-balance to the Heritage Lottery funded ‘NARM Naming And Role Model: Highlighting African British Male Role Models 1907-2007’ book and accompanying video project I was working on for BTWSC, I decided to fund a female-focused DVD entitled ‘What They Said I Should Be: The Story Of African British Female Movers & Shakers’.

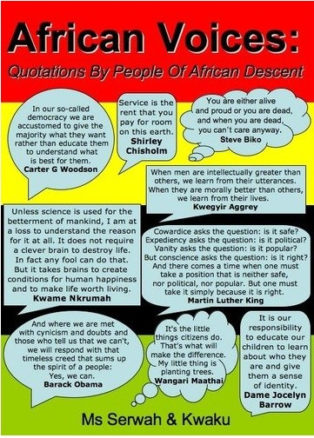

One of the features of the DVD was a chapter where each contributor offered a piece of advice. Dame’s resonated so much with me that it found its way inside and also as a pull quote on the cover of ‘African Voices: Quotations By People Of African Descent’, a book I co-edited.

The quote reads: “It is our responsibility to educate our children to learn about who they are and give them a sense of identity.”

Another thing which resonated with me from the interview, was that she had no reservations about pointing out that she came from a middle-class Trinidadian family. Quite frankly, I found it refreshing, considering the many interviewees who tend to wear their working class, fact or faux, on their sleeves.

The African British life isn’t a monolith one synonymous with working class. Interestingly some, including those who’ve definitely established a posh, middle if not upper class life, perhaps for credibility or authenticity, feel the need to project a working class image.

Anyway, of the seven women featured, the only one I regularly kept in touch with, apart from Dawn Butler, who is my MP, was Dame. I recognised her value as living history. As someone who writes about, and delivers programmes on, British African history, I always had one reason or another to call her up to find out or corroborate some piece of historical information I’d come across.

At first, I’d introduce myself, saying: “This is Kwaku.” But before long, that became redundant, as there was recognition and a welcoming voice at the other end of the phone line. At times I’d call simply to ask how she was doing. She was always upbeat, and I often remarked on her positive response. Very occasionally she’d mention an ailment she was dealing with, but even then, she was of good cheer. She did however chase the sun, by spending the winter months in the Caribbean.

The second project Dame contributed to was the ‘Look How Far We’ve Come: Commentaries On British Society And Racism?’ DVD and accompanying book.

I initially wanted to interview her at the University of London Institute Of Education. The reason was that not only was it close to her flat, but that’s where she came to complete her post-graduate studies in education. It was also where she was seconded in 1979 as a senior lecturer in education for three years. During that period she helped popularise a multi-cultural education regime from community to tertiary education level.

Interestingly, an African staff I approached who supported African history programmes in the university, saw no value in offering a free room for a programme highlighting someone like Dame who had contributed to the university’s development. As luck would have it, after one false start recording in Dame’s local restaurant where an excellent interview was marred by noise, it was a European staff, who recognising Dame’s role in British history, deemed it “an honour” to offer his office for take two of the interview.

I’m sure Dame was pretty much fighting racism from the time she first arrived in Britain in 1959. In December 1964, she was among the few community leaders who had a private audience with Martin Luther King, when he stopped over in London on his way to collect his Nobel Peace Prize in Norway. One of the suggestions King made was the need for a local organisation to confront racism. Dame became a founding member of CARD (Campaign Against Racial Discrimination) – one of the organisations that helped bring about the 1968 Race Relations Act, which extended the ambit of the 1965 Act by covering accommodation and employment.

In 1972 she was awarded an OBE for her race relations work. Of course fighting racism includes creating opportunities for discriminated groups. This Dame did by using her position on various boards to create opportunities and a more level playing field for people from AAME (African, Asian and Minority Ethnic) backgrounds in various fields.

She told me that when she served as a BBC governor from February 1981 to December 1988, she made changes not by making demands, but from the sort of questions she asked. One of the outcomes of her questions was that by October 1981, Moira Stuart had moved from BBC radio to become a regular face on BBC television news programmes. Other outcomes were the training of young people from AAME backgrounds, who got jobs in the BBC and other media outlets.

It’s a pity today’s news broadcast producers seem ignorant of Dame’s contribution to broadcasting, for which she was recognised and made a dame in 1992.

She was invited by the Inns Of Court Law School to chair an inquiry into “why black barristers and women barristers were not being successful in their training.” This enquiry led to a change in the then centuries-old tradition of confining law training to London, by making the training available in six other parts of the country. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons why she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree by University Of Greenwich in 1993.

Dame also used her connections with influential people to move forward the race equality agenda. For example, she got Lord Sieff to employ African girls on frontline duties, such as sales staff in the Marks & Spencer stores in London’s West End. She also used the association with the retail boss to get the manager of the Brixton branch to hire African sales staff.

She was part of a self-help group called Each One Teach One, which helped African Caribbean children with their studies, and helped their parents understand how the British education system worked.

In the 1980s, she noticed that adults, particularly from the African Caribbean community, were not seeking promotion into managerial roles, because of lack of literacy skills. So one of the ways she used her profession as a teacher and teacher trainer was to develop the Caribbean Communication Project, which taught literacy skills to working adults. It was on a visit to this project in Brixton that she discovered the colour bar in the local Marks & Spencer. She also developed in-house literacy training programmes for employers, such as Ford Dagenham.

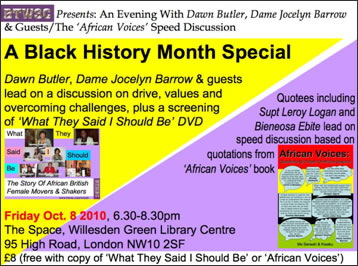

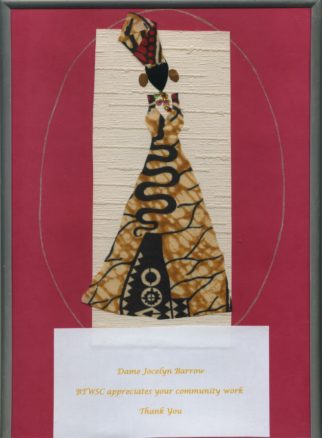

We appreciated the support Dame gave to BTWSC projects, and looked for an opportunity to recognise her. We had intended to present her with a hand-made card to show our appreciation for her activism at a 2010 African History Month event. She and fellow contributor Dawn Butler were to be speakers at the screening of the ‘What They Said I Should Be: The Story Of African British Female Movers & Shakers’ DVD.

She could not make it on that occasion, but we were delighted to honour her at the ‘Look How Far We’ve Come: Getting Racism Back On The Agenda?’ conference in 2015. She was interviewed on stage and presented with the card.

Click here to watch 1 minute video of BTWSC 2015 Dame Jocelyn Appreciation Presentation.

Following the hullabaloo caused by the screening of the Sky Atlantic docu-drama series ‘Guerrilla’ in 2017, we organised ‘From Mangrove Nine To Guerilla’, an event in which we discussed the portrayal of African British activism and history in film and TV. Dame made a pre-recorded audio contribution.

Anyone who’s read Dame’s biography would know of her high profile appointments. For example she was a founding member and general secretary of CARD (Campaign Against Racial Discrimination), the first African female governor of the BBC, founding member and deputy chair of the Broadcasting Standards Council, governor of the Commonwealth Institute, etc.

She was also involved with several less high profile community activities. For example, in the mid-1970s, her community work included being a trustee of the Marcus Garvey Memorial Trust, an organisation which aimed to build a library named after the pan-African icon in the London borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. She was also chair of the ‘Black People in Britain: The Way Forward’ Post Conference Constituent Committee, which was concerned with moving forward AAME community interests.

Although I regret not being able to call her when she crossed my mind a few weeks ago, I’m honoured to have known her, and grateful for her willingness to answer the numerous questions I called to ask about. I’m especially grateful that she personally invited me and my wife to her official 90th birthday party last October at the South African High Commission, which was organised by her Trini Focus Consultancy colleagues Prof Chris Mullard and Ansel Wong. This must have been the last time many of us gathered in South Africa House saw her.

An African proverb says: “When an old person dies, it’s like a library burning”. That indeed is the case with the passing of Dame. This reminds me that a while back I suggested that historians interview living history personalities, who played a key role in contemporary African British history. Sadly, Dame is now off that select list. But there are a few other living history personalities around, so let’s tap into their lived-in experiences, before it’s too late.

Kwaku is a history consultant. BTWSC events are posted at www.AfricanHistoryPlus.eventbrite.com. For resource enquiries, btwsc@hotmail.com.